|

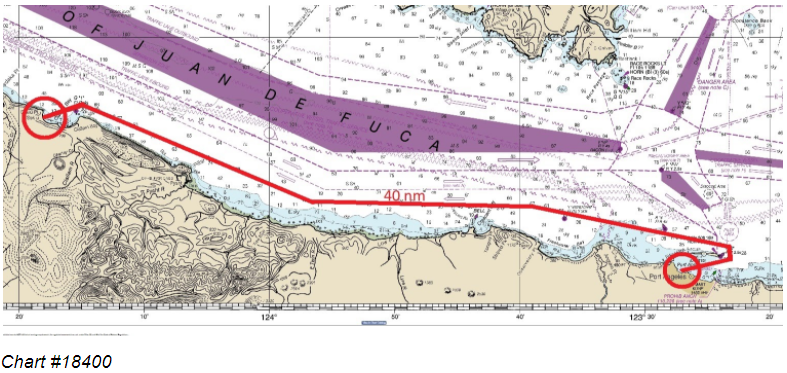

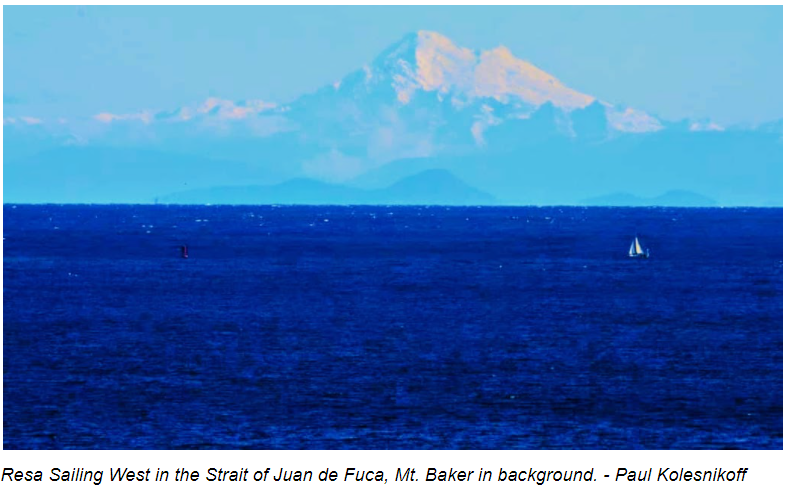

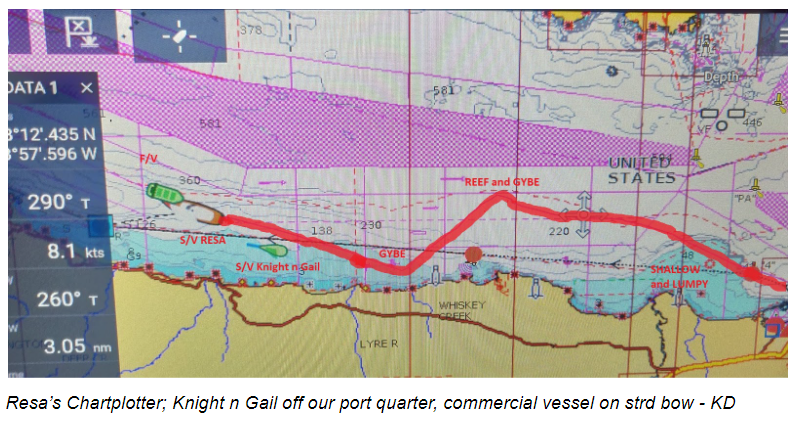

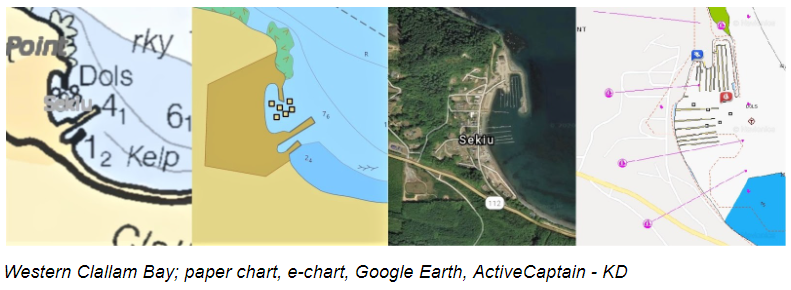

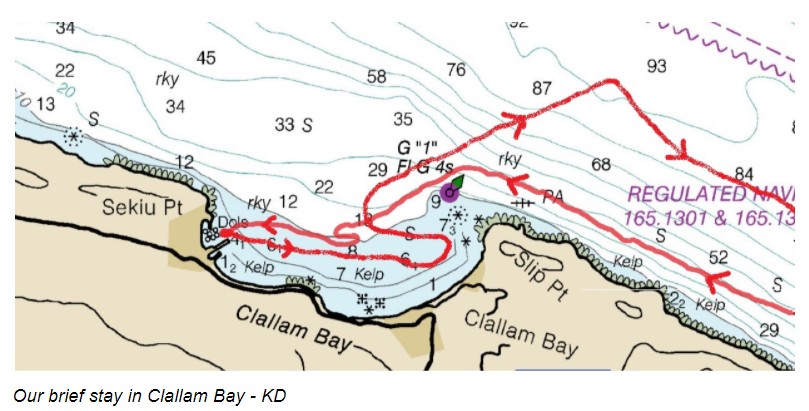

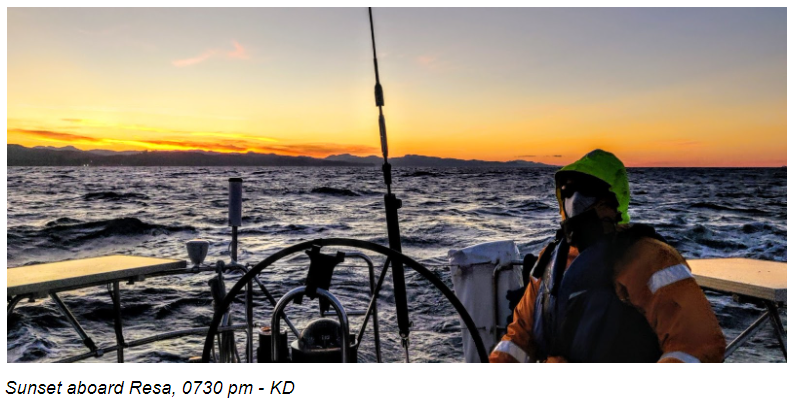

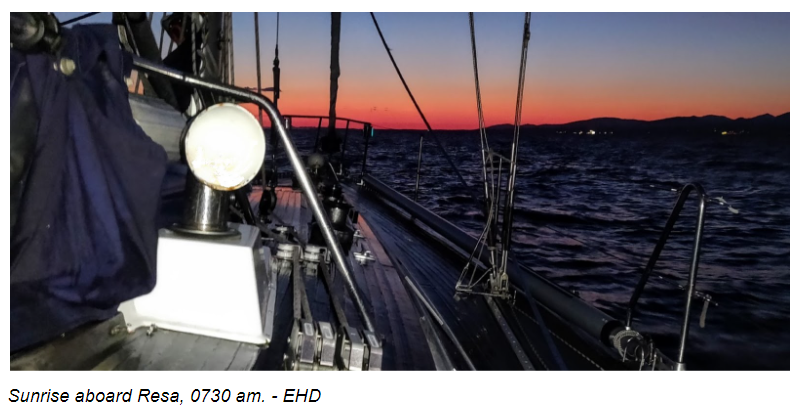

Saturday, October 24th at 10am, we slipped the dock lines, stowed the fenders, and exited Port Angeles’ Boat Haven marina. A few minutes later Resa, our Sweden 41 sailboat, met up with the Sea Scouts aboard their sailing vessel Knight n Gail . We had been wanting to sail Resa points west for some time and were equally eager to help Jared and his Sea Scouts fulfill their “long cruise” requirement. So, Erika, Rebecca, Elliot and I booked passage for Clallam Bay, roughly 40 nautical miles west of Port Angeles. The plan was to sail eight hours to Clallam Bay, arrive by 6pm, tie up or anchor for the night and return to PA the following day. The good news, we shaved two hours off our intended transit time there. The bad news, we had to slog another 16 hours back to Port Angeles almost immediately after arriving in Clallam. The following is an embellished log of our 23 hour non-stop adventure out West...and back. The day’s wind was forecast to send us east with a following and blustery breeze around 25 knots with gusts near 30. For the first two hours the current would be directly on the bow, reducing our speed over the ground. Fortunately the flood would reverse to an ebb by noon and help carry us west the rest of the day. Still in the protection of Port Angeles harbor, the crew pointed Resa directly into the cool easterly breeze, hoisted the main to it’s full and rolled out the genoa. Off the starboard quarter, not a half mile behind us, Knight n Gail followed suit. We trimmed the sails closely, keeping the pilot, navy and coast guard stations safely off our port beam. At the end of our maritime parade of buildings, Resa tacked around Ediz Hook’s red buoy, officially entering into the more exposed Strait of Juan de Fuca. As if we were entering an empty highway from an onramp, Erika turned us sharply downwind, Rebecca eased the sheets, and Resa accelerated westward. Next stop, Clallam Bay! Although we had clear skies and sunshine throughout the trip west, the daytime temperature was a brisk 50 degrees while windchill dropped it to the low 40’s. In a short time all of us had our entire kit of foul weather gear on, adding accessories throughout the day, a warmer hat here, extra socks there. In the Strait during the month of October the average high is 57 degrees while the average low is 47 degrees. During our planning stage of the trip I noticed on this particular weekend, and this weekend only, the temperature would drop to a frigid 32F with strong northeasterly winds. It looked suspiciously like what locals call the Fraser valley outflow. Fortunately Resa had a diesel heater to warm our bunks at night during this meteorological bit of bad luck. By noon the currents in the Strait had switched from the weaker flood to the stronger ebb, increasing our speed over the ground up to a knot and a half. Reaching speeds over eight knots much of the day made for a rollicking ride along the tree studded, rocky coast of the Olympics. As we passed the northern perimeter of the shallow escarpment around Angeles Point, and Elwha’s effusion of sediment, the seas became noticeably lumpier. Later Jared had shared with us that this was where Night n Gail’s crew, understandably, lost a few portions of rations over the side. Fortunately it wasn’t long before we sailed back into deeper waters where the choppy, wash machine-like conditions were replaced by the larger rolling, and periodically breaking, six to eight footers. Although the seas were larger, the ride was much smoother in the 40 to 70 fathoms under our keel. Everyone aboard Resa settled in a corner of the cockpit, some with grins on their faces, taking turns steering Resa down the quick moving moguls of water. With a couple whale sightings off our port beam (possibly the Grey’s heading west then south for the winter) and the tidal current switching 180 degrees in our favor, the sail to Sekiu was feeling quite satisfying. In fact it was such an absorbing ride we didn’t notice lunch time had come and gone. Keeping the northeasterly winds and seas on Resa’s starboard quarter made for a comfortable ride so we kept her course. This tack made for a favorable heading westward but sent us further offshore. In other words, we were quickly approaching the southern boundary of the large shipping lane as well as the canadian border, which was strictly closed due to covid. We already had a few mostly pleasant run-ins with Canadian customs and their coasties during other trips in the summer. A gybe was imminent if we wanted to stay clear this time, which we did. Instead of jibing with full main under near gale conditions we turned Resa a bit up wind and threw in two reefs. Bearing back to our original course speed changed little but the sail was more manageable for the coming maneuver. After the gybe Resa returned to port tack, driving us back towards Washington's rugged coastline. An hour or so later we set up for another gybe, this time near Whiskey Creek in about 10-12 fathoms of water. The large, hard to miss promontory known as Pillar Point, was dead ahead. We steered a couple points starboard of the enormous headland, keeping us close to shore and well within the west bound traffic lane designated for “slower” vessels like us. With the Knight-n-Gail in sight off our port quarter, we settled on our last tack for the long leg to Slip Point, our final waypoint before turning into Clallam Bay. Jared, the Sea Scout Skipper reported via VHF that things were going well, and in fact witnessed a couple Orcas in their vicinity. We reported back that we did not see the Orcas but were also enjoying the blustery ride. This was an opportunity to go below and collect a few snacks before all our attention was negotiating Resa’s first time in Clallam Bay. By then it would be all hands on deck. Sitting down to a warm meal inside a warm boat would have to wait until Resa’s anchor was fast to the bay. Sekiu has a population of 62. But during the summer the little town is a bustling fishing resort. For a few months hundreds of small recreational and commercial vessels vye for Sekiu’s proximity to the Straits fauna but also hosting protection from strong Northwesterlies. In September, according to our earlier findings, maintenance staff pull the docks out of the water for the season and close down most of the facilities until the following April, leaving the pillings free of course. Mooring between the pilings or setting a hook nearby was our intention. By 4pm Resa reached Slip Point’s green buoy. The buoy, positioned about a quarter mile off Clallam Bay’s northeastern end, buffers vessels from a dangerously shallow rocky reef. As we passed the point it didn’t look any more treacherous than the bay we were entering. The tide was high but the wind waves were higher, filling the bay with a uniform swath of stirred up white caps from the strait to the seashore. It was very clear that Clallam was not an all-weather anchorage especially during a 25 to 30 knot Northeaster. Mother nature would happily sail us right onto the beach if we didn’t mind her. Erika quickly turned Resa into the wind as Rebecca and I struck sails. We motored down wind, towards the marina’s jetty at the western edge of the bay. Since the waters in the bay were a bit chaotic, we continued towards our plan to tuck in the lee of the breakwater. Both paper and electronic charts showed 24 feet near the south end of the breakwater. Resa’s fin keel measures eight feet down from the water line. All of our senses would be on high alert, not due to the charted depth coming into the cove, but because we did not have a functioning depth instrument. A month or two earlier our depth sounder had failed and was to be replaced during our annual haulout, which was already on the calendar in November. But I jumped at the chance to squeeze in one more cruise before having to knock out a laundry list of winter projects. Not having an electric means to measure depth concerned us but wouldn’t stop us. We would be in the company of Vancouver or Vázquez de Coronado and carry a calibrated rope with a lead weight at the end. Our buddy boat, on the other hand, drafted only six feet and had a functional sounder. If we could locate a safe and appropriate refuge in Clallam Bay so could Knight n Gail. During our preplanning we had come across very little information regarding Sekiu other than the marina’s seasonal sounding data. It was noted that the fuel dock stood in six and a half feet at mean lower low tide. Yes, a red flag, yes, a bit out of date, but information we took into account nonetheless. Primarily, Resa will avoid the area near and around the fuel dock, especially at lower tides. With the little data from the local charts, little local knowledge, no local communication and with the weather that it was we proceeded to follow a track around the breakwater and into the cove at a tactful speed. Before we could consider the out of date red flags, Resa’s keel kissed the bottom and lurched to a stop. Erika and I immediately turned to each other with that “Did we just hit the bottom or did we just HIT BOTTOM?!?! look. We have felt these soft, mushy meetings in the past and it's always a bit unnerving but this felt more ominous than usual...lee shores, stormy seas, cold winds, empty stomachs, etc. etc. Erika promptly turned the wheel hard to port and nudged Resa back into deeper water. The old school lead-line I had laid on deck earlier, ready to “feel” our way into the cove was immediately side-lined. We back-tracked to the middle of the bay, far away from the mysterious shoal lying right in the middle of plan A. We hailed Knight n Gail and warned them about the shoal we dismally discovered off the breakwater. After a chat over VHF radio Jared understood our concern and agreed to cautiously test the entrance with their depth instrument. If the depth was near eight feet, they would be able to sneak in and drop their sea scouts off as planned. Resa stood by, bare poled, rolling back and forth in the wind and waves, for a report from Knight n Gail. This was about the time we planned to break some bread and pop a cork. Instead, our minds were still on the small tempest behind us and Jared’s take on the situation. Time seemed to have crawled knowing decisions had to be made. Eventually the VHF radio crackled to life...damn, Knight n Gail confirmed the muddy blockade. Time for another plan. While the sea scouts were being taxied off Knight n Gail via their inflatable tender, Resa galloped across the bay to explore alternative anchorages for the night. There would be no tying up or anchoring anywhere near Clallam Bay’s western lee shore that evening. During Jared’s three or four trips shuttling the scouts safely to shore and their awaiting parents, we had time to establish the eastern side of the bay was just as exposed as the west. And without a swift, straightforward way to judge depth or fix a set of bearings throughout a dark and blustery night, the plan to put over in the bay was quickly dwindling. The sun had just set behind the mountains, it was time to confer with Knight n Gail. After a brief exchange regarding our comfort levels staying in Clallam Bay or heading to Neah Bay (rumor was Neah Bay was also strictly closed due to covid), we agreed the least risk was to head back to PA, together. We doggedly turned Resa into the gums of the slightly abated easterly, hoisting an abridged version of the sails. By 6 pm we abandoned the darkening bay and marked a course for Port Angeles. Our initial thought was to beat up the strait but noticed Knight n Gail’s southwesterly heading under power alone, so we struck sails, fired up the 40 hp diesel and laid a new course alongside Jared and his shorthanded crew-mates, Chet and Ozi. As darkness fell so did the air temperature and by 7 pm it was already... really... flipping... cold. By 2 am the temperature was forecasted to go polar. I was hoping we could be in PA by midnight and even shared my dreamy optimism with Erika and Rebecca but a 2 or 3 am arrival time was more realistic. We would feel the freeze for sure. By 9 pm the chemical hand warmers were dispatched with much gratitude. Unfortunately, the wind was back up to near 25 knots with the corresponding six foot seas square on our nose. Our easterly progress deteriorated enormously. No more slipping down the backsides of these craggy waves, punching thru and plunging down was the new M.O. The frigid 25 knots of ocean spray shot across the cockpit with every six foot drop of the bow. For hours Resa’s chartplotter displayed a dispirited velocity of two to three knots with a new arrival time closer to 7 am. I blocked out the prospect of another ten hours at sea and focused on the conditions at hand. By 10pm, Erika and I began ninety minute watches to reduce exposure and catch some shut-eye. With two chemical hand warmers in each pocket and one in each boot we were barely tolerating sixty minutes amidst the cold, wet blackness of the pacific northwest. Rebecca kept company with Erika for first watch, ultimately retiring to the starboard settee for some near impossible respite. I returned topside to relieve Erika so she could also take a break from the elements. Having to hand steer continuously on long, tiresome passages in the past, we were grateful this time to have an autopilot that could hold course in such a pitchy, perilous place. We relied heavily on our AIS and RADAR, amplifying, or simply just detecting, what our diminished senses could not. Although the commercial traffic is somewhat light in the strait, we did alter course a few degrees to stay well clear of a large fishing trawler at 1:15 am and a tug n tow later around 3:00. Sometime near midnight I went below to use the head, and again about every two hours after that. Maybe I hydrate too much, I don’t know. Anyway, it's always a treat taking off five layers of wet clothing in a space the size of an old telephone booth that is being violently jarred up and down all while getting an unexpected cold shower from the newly leaking solar vent from above. A leaky vent, another addition to our growing project list. Each time a bit more damp, and maybe bruised from peeing in what felt like a paint shaker, I would relayer and quickly parkour my way back topsides. During one of my hasty trips to the head I noticed a soaked towel on the chart table. Everytime seawater washed over Resa’s deck, which was often, a deluge of water would pour through worn out seals from a cabin window and the main hatch. Evidently the problem had been concealed up until now. Erika temporarily buffered the area from the occasional cascade with a couple beach towels. I just hoped the sodden charts and carpet below would dry out okay. Our trip out west compared with the return back was becoming quite a contrast. With twenty miles to go, It was time to look on the bright side. Resa’s current boat speed of one nautical mile per hour made it easy to calculate our ETA. Yippee, we’re moving now! Erika and I were officially ready to put this trip to bed, literally. Don’t get me wrong, night passages can be extraordinarily rewarding, a time for stargazing and personal reflection, satisfying the primordial itch. But motoring directly into a six foot chop with 25 to 30 knot ice-cold headwinds was making it difficult to think of anything else other than the sub freezing wind chill factor. The wind, specifically the wind direction, was not only impeding our forward progress but also eliminating all nearby refuges. Only three or so geographical indentations can offer shelter from the prevailing westerlies between Neah Bay and Port Angeles; Freshwater, Crescent, Clallam and, less so, Pillar Point. But all of these hidey holes become open sores when north and easterly gales hit. So, whether it took us eight hours or twenty eight hours, our focus remained on Port Angeles and our buddy boat, Knight n Gail. Throughout the journey home Knight n Gail stayed about a half-mile or so off our stern. We would spot only her lonesome white steaming light fluctuating in and out of the black seascape, but mostly tracked her position via AIS. Every few minutes I would pop my head out in the full force of the weather, scout Resa’s surroundings then quickly hunch back in my corner. Here I would watch the waterproof tablet connected to the house MFD (multi-function-display) via wifi for any changes in course or traffic, but in truth I was primarily transfixed on our boat speed and arrival time. Days later, Jared mentioned, aside from using their electronic navigation, he also kept a steady eye on Resa’s solitary stern light amongst the maelstrom. At one point Erika tried to hail Knight n Gail on the VHF radio and didn’t get any response. She fathomed all was well, continuing to confirm that the vessel was still moving and on course with our automatic identification system. Hour after hour the diesel engine popped and spit as Resa plunged and splashed in the cold, wet, dark of the Strait. I was off watch, dog-tired, desperately trying to melt into my bunk with its cozy blankets and soft pillow when I heard a mutter of voices on the VHF radio. I was hoping it was just routine traffic and Erika was confirming a captain’s intention nearby. But the relentless pitching and rolling suddenly ceased. It felt as if Resa had stopped in a flat sea but the engine’s continued high rpm said otherwise. The drastic change of motion was euphoric but the feeling was short lived. “Knight n Gail’s engine is disabled” Erika informed me, “we are heading back to help”. I rolled out of my bunk, added the two top layers of gear back to the four base layers I still had on, pulled on my boots, put on my hat(s) and gloves and climbed into the cockpit. Erika handed me the charting tablet. Resa was about a mile north of Crescent Bay, heading west again, AND clocking over nine knots, a whopping eight knots faster than on our easterly heading. What? Our first concern was Jared and his crew, Resa’s questionable speed anomaly would have to wait. Fifteen minutes later we were safely off Knight n Gail’s beam. The strait was still rolling with six to eight foot chop and 20 to 25 knot gusts. After a quick update between the boats, it was confirmed that their engine was definitely the culprit and out of commission. Knight n Gail was clearly adrift, rolling violently back and forth with each windy swell...an uncomfortable and dangerous motion for any weary crew. We agreed that the USCG would be a safer, more efficient fit to tow the Knight n Gail back to PA. Jared made the pan pan call while we held our position as closely as possible . About 20 minutes later a boat appeared from the dark and began sweeping a large spotlight over Resa. It was the 29 foot USCG response boat from Port Angeles. We radioed back stating the vessel in distress was a few boat lengths down wind. Another 20 minutes and Knight n Gail was safely under tow. That was our que to continue the slog east. It was 4:30 and we had twelve nautical miles to go. By 5 am the twin 225 outboard engines on the USCG Defender Class Response Boat had slowly built up enough power to tow Knight n Gail at a good clip. It wasn’t long before the two boat’s stern lights were dots on the horizon, leaving us to settle back to our abnormal watch routine....shiver until you can’t stand it “watches”. Erika plainly earned a turn to go below after her unexpected double watch. I swigged some water, took a bite of a breakfast bar and crawled back into my chilly corner of the cockpit. The Strait was still dark, the air was still freezing, and the sea was still lumpy but the wind was finally starting to weaken. I picked up the tablet and checked our speed over ground for the millionth time, three point two...three point seven... four knots and climbing...I felt a wash of joy. We hadn’t made four knots in over twelve hours. Our new ETA was roughly in three hours, way better than the twenty hours we had dreaded earlier. Consequently, not long after the wind dwindled, the sea began to flatten. I was almost enjoying myself again. Things were starting to look up in more ways than one. By 0700 the red-orange glow of twilight diffused over the eastern horizon. Witnessing a sunrise at sea traditionally evokes an emotional high and though I was cold, wet and exhausted this particular morning still didn’t disappoint. For the next half-hour my attention was lost on the blossoming colors in front of me, almost bestowing a desire for a photo or, perhaps, a paint set. Erika awoke by 0730 to witness the scenic daybreak and snapped the picture I was too sluggish to take. By 0800 the sun broke the eastern horizon and, immediately, we felt a welcoming warmth on our faces. I chuckled at the thought that our eastward passage was perfectly bookmarked between the sunset and sunrise. Slipping along the glassy liquid at nearly seven knots, Resa followed the outside of the Port Angeles Harbor breakwater east, pivoted around the red entrance buoy and laid course for the last two miles home. Rebecca must have sensed our close proximity and came out on deck to help secure the fenders and lace the dock lines. Once everything was in place the gang quietly lolled about the frost covered decks, soaking up the morning sun probably thinking how irritatingly tired we all were. I was begging to heed the call of my horizontal hay stack below. After placidly passing all the harbor landmarks from east to west (CG station, Coho ferry, etc) Resa was back in her slip officially ending our jaded jaunt by 0900 sharp, just short of a full day and night cycle later. And BTW, It’s good to know that four zombies can tie up a boat, clean up the galley and pack all their gear before you can say dead tired.

Following a deep midday slumber we returned to the marina to remove the dampened chartbook and soused carpets caused by the leaks so rudely exposed during the passage home. Lucky us, the calm, sunny day would greatly assist in the drying action. After laying out all the wet stuff topsides, Erika and I both chuckled, probably with a wee bit of bite, at the contrast between last night's temputeousness and today’s blissfulness. Doubless, It would have been a tranquil trip home Sunday afternoon, but, as our sixth sense told us, sticking it out in Sekiu could have ended awkwardly, or worse. Boat trips frequently don’t go according to the original plan and one’s expectations can be dangerous, especially for everyone else aboard. For us, leaving Sekiu for another day and managing the strong winds and waves in deeper water, away from the less familiar shoreline, was for the best. Someday we will sail back to Sekiu and stick around a bit longer using our new working depth instrument and a bit of local knowledge gained from our non-stop adventure out west. - KD

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorA UCSC graduate in Marine Biology, Keith holds a 100 ton USCG Capt. License and is an ASA/US sailing certified instructor. Archives

March 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed